Cannibal Run

first featured in 4x4 magazine, august 2018

The early Jeep Wrangler was a very fine vehicle, but it needed to be modified to get the best from it. Not many have been treated to quite as extensive a set of new bits as the one Kev Hartshorne built a few years ago, though – which started when he decided to cannibalise the monstrous old Chevy Blazer that went before it.

Ever since the Land Rover Defender went out of production, people have been flocking towards the Jeep Wrangler for their next off-road project. But the Wrangler had already been around for a long time before Solihull pulled the plug on its own old warhorse – and while it’s only ever been a minority choice since its arrival here in 1992, most of the vehicles that made their way to the UK back then have long since been turned into hardcore off-road playthings.

The latest Defender, a limited-edition continuation model announced earlier this year at a cost of £150,000, is powered by a hefty great V8 engine. Back in the 1980s, of course, Defenders were available as standard with V8s – something you were never able to say about the Wrangler, which has always come with four and six-pot units.

Ironically, then, the number of V8-engined Wranglers in the world probably dwarfs all those Defenders still packing RoverV8 power. That’s because America’s off-road terrain demands seriously big tyres – which in turn demand bags of lazy, low-down torque to keep them turning at typical rock-crawling speeds.

But putting V8s into Wranglers is definitely not just an American thing. Some years ago, we came across Kev Hartshorne, a man who it’s safe to say likes his 4x4s a bit more radical than most.

Prior to the YJ Wrangler you see in these pictures, Kev used to own a Chevy Blazer. It was huge, massively lifted and shod with 38” tyres, and while its presence on the road was roughly comparable to Hulk Hogan turning up in your local corner shop, it was far too wide for most green lanes. Or most garages, come to that.

Hence this Jeep. It’s from the second year of UK imports, back when Wranglers arrived at the docks with their steering wheels on the wrong side and were converted to RHD before delivery to Jeep’s UK dealers. When Kev bought it, it was more or less standard – but it didn’t stay that way for long.

At this point, we say goodbye to the Blazer. But we don’t say goodbye to many of its parts, which were stripped off to be reused on the Wrangler before what was left of the big old Chevy found itself being weighed in.

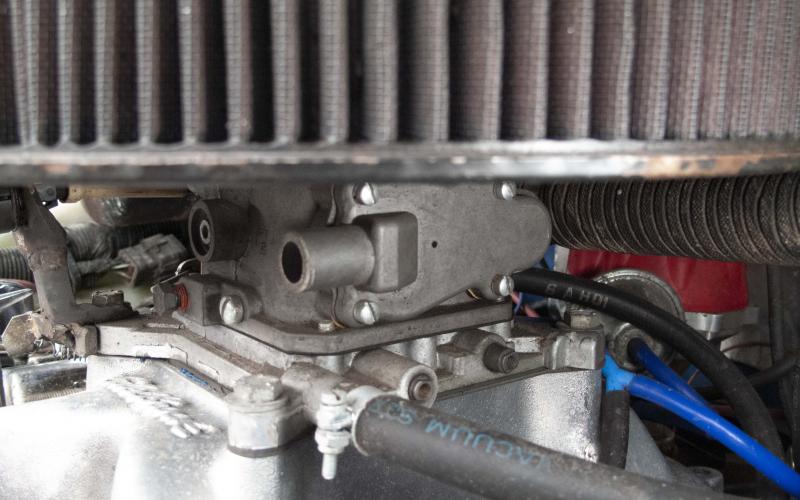

Needless to say, one of the parts Kev retained was the 5.7-litre V8 engine. Despite its small footprint, the Wrangler’s engine bay has plenty of space in it for much more than the standard 4.0-litre straight six, so this was an easy swap-in. Kev did have to fabricate new engine mounts, and there’s a custom radiator in there now,

but the biggest job was probably removing the supercharger he’d bolted on to help it shift the Blazer around. He did retain its high-lift cam and header conversion, however, meaning is was dishing out something like 300bhp, and that’s enough to be going on with.

Something else he retained was LPG fuelling, using an Impco 425 carburettor and a 120-litre fuel tank for storage. He reckoned this was good for a range of more than 300 miles while, only costing around half as much as petrol, without any noticeable drop in performance – which is good, because rather than going bi-fuel he binned off unleaded altogether and ran the engine on gas alone.

Beyond the engine was a TH400 automatic gearbox fitted with a B&M shifter upgrade for precision changes and an auxiliary oil cooler,

and this in turn spun a custom-built Atlas II transfer case. That lot makes up a very popular combination among US rock crawlers, and what’s good on the trails of Moab is pretty much sure to be good on anything you can find over here.

Moving on down the drivetrain, the propshafts are HGV-spec GKN units and the axles are Dana 60s – something else the Blazer donated when it laid down its life. When you’ve got that much power going out through a set of ultra- grippy 37x13.00R16 Super Swamper Boggers and a driver who’s cheerfully willing to admit that he likes a bit of a go on the loud pedal, your transmission needs some serious strength to cope with the shock loadings that are sure to be coming its way.

This is especially the case as the YJ-era Wrangler rode on leaf springs – which, while they can be made to flex very capably, are

still more prone to lifting wheels than a more coil-sprung set-up. Still, a Detroit Locker in the rear axle helps prevent any traction losses this might cause – as of course does a suspension set up which, as you can see, provides as much articulation as it does height.

On the subject of height, the overall lift

is about nine inches. This comes from a combination of taller Skyjacker leaf springs and the fact that Kev mounted them on top of the axles rather than underslung.

The springs themselves were another hand- me-down from the Blazer, which might get you pondering on the ride quality they provide. If they can hold up all that metal, after all...

Kev did admit to us that if money had been no issue, he’d have preferred to convert the YJ to coils. But with about a metre of travel at each corner, he’s not exactly doing badly.

The articulation comes from a combination of Teraflex extending and twisting shackles and long-travel Pro-Comp ES9000 shocks, as well as polyurethane bushes all-round. ‘The shackles are very trick,’ Kev told us, ‘and bring a great deal

of flexibility to the leaf-sprung configuration.’ In Britain, we tend to equate cart springs with stiff travel and a bone-shaking ride, but the Americans were still developing technology in this area long after we’d all started chopping up old Range Rovers instead – and, on Jeeps like this, it shows.

Going back to the tyres, they ride on Pro- Comp rims and are fitted with heavy-duty inner tubes from a tractor. Nothing wrong with a big of overkill in this area, and the same can certainly be said of braking – where the Dana 60s have plenty in reserve beneath such a light truck as the Wrangler.

Naturally, the brakes are fed by extended hoses, and it won’t come as a surprise to hear that the standard steering set-up wasn’t about to work with all that extra height either. Kev retained the standard drag link and track rod but had to turn them round and relocate them above the springs – something he says took a lot of trial and error (and therefore patience). Shoving them this way and that, the Wrangler’s standard PAS box is retained, albeit with a stronger chassis brace.

Other strong things Kev put on the Wrangler include a diff guard on the front axle, along with

heavy-duty bumpers all-round. The front one,

a Warn unit, is home to a Britpart DB12000i winch, while the rear is a tubular steel job with an integral spare wheel carrier.

Something Kev didn’t bother with, on the other hand, was waterproofing, whether for

the engine or the electrics. His rationale was simple: with so much height under the vehicle, its vulnerable bits should be well out of the reach of water. And to be fair, if he did get in deep enough to drown the engine, the vehicle would be the least of his concerns.

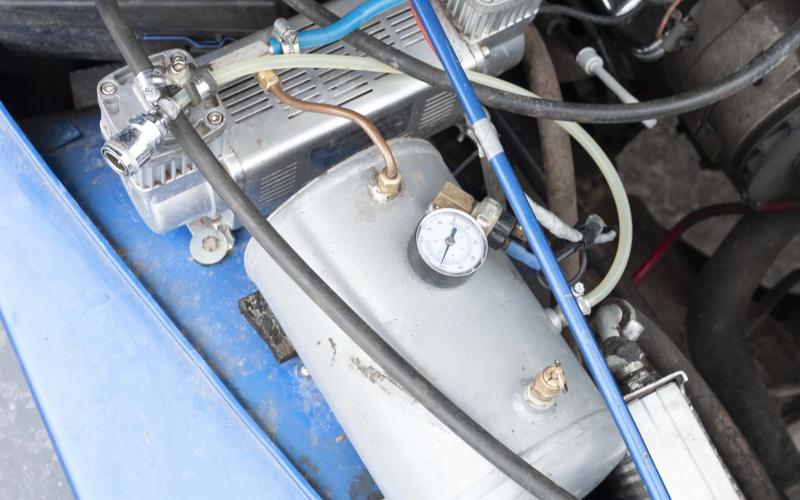

Elsewhere, it’s all good, standard everyday common sense. There’s a pair of Optima Yellow- Top batteries, which are fed by a twin alternator set-up, better seats, a rally-spec digital speedo and on-board air – which, in continued common- sense news, powers a 120psi train horn as well as the more prosaic tyre inflator.

Well, there nothing quite like the sound of a Union Pacific coming across the Prairies to warn you that there’s an all-American four-wheeler on the way. Unless, that is, it’s the sound of the all- American V8 engine propelling the four-wheeler in question. Talking of which, was Kev happy with his choice of Chevy motor? Almost. When we spoke to him, he told us he was planning to replace it with something more sensible. A 7.4-litre big-block, obviously. Ain’t nobody brings anything small into a bar around here...