N n n n n n Nineteen

The 19th running of the 1000 Rivières randonnée was possibly the toughest ever. With terrain that stood comparison to the fearsome Trophée Cevenol, it was more than enough to set your teeth chattering… and that was before the freak rains that seemed to wash much of the countryside away

Hands up all of you who’ve ever driven past a ‘road closed’ sign, thinking that since you’re driving an off-road vehicle the fact that there’s no road at the moment shouldn’t apply to you?

Normally, the worst that happens is that you get frowned at by people in lesser cars who can’t stand to see anyone else getting ahead by bending the rules. Sometimes you find yourself having to turn back and take a couple of miles’ detour, but that’s as bad as it gets.

So when you’re in a mountain valley after dark and a sad little tin plate sign saying ‘route barrée’ is all that’s coming between your convoy of battle-ready 4x4s and the only direct road to dinner, you’re unlikely to be too daunted. Not even when there’s another one half a mile further on.

But then your headlamps pick out what appears to be a line drawn across the road ahead. Beyond it, blackness. You get out to take a look, as best you can in the darkness… and though you can’t see much, you can hear roaring water somewhere out there. As your eyes adjust to the gloom, in the full beam of your trucks’ assorted lights, you can make out a bridge… or half a bridge. Where the other half used to be is a chaotic jumble of rubble and what look like whole trees.

In the early autumnal months leading up to this year’s 1000 Rivières, the south-central region of France was hit by the sort of freak rainfall you normally see in disaster movies. All off-roaders are used to dealing with ground conditions that have been drastically altered by the weather, but this was something special. Shallow runoff streams were gouged out into unforgiving mountain gulleys, incised hillside tracks were peppered with mini landslides, loose soil and small stones were washed away to turn smooth tracks into minefields of jagged rock. The 19th running of this classic southern French randonnée was going to be a good one.

Even then, it wasn’t until we saw the remnants of that bridge that we realised just how savage the flash floods had been. This wasn’t a rickety old lash-up on a little-used mountain trail – it was the sort of bridge that carries cars, buses and lorries all day long, and it looked as though some massive foot had appeared out of the sky and casually kicked it out of the way.

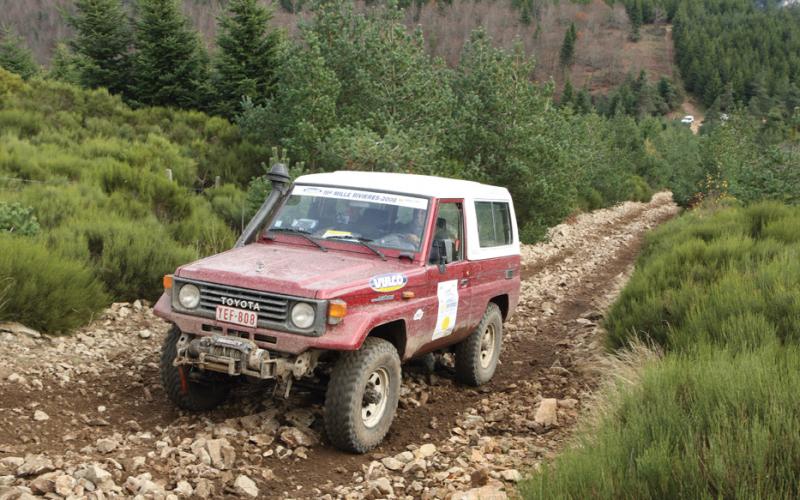

Even by now, however, the 1000 Rivières had already bitten, and hard. We had survived a savage first day, thanks largely to the fact that we needed to cut out part of the morning’s route which, unknown to us, included one of the most extreme tracks in the event’s entire history, but arriving at the lunch stop to find a Belgian Land Cruiser parked at the side of the road, its roof stove in by a vicious end-over-end roll, didn’t half concentrate the mind.

We later heard that this was one of two vehicles that went over during the first day. And it was taking some serious concentration on the part of drivers and spotters alike to keep that tally to a minimum. A couple of Brits we spoke to said this particular track, an intense, twisting downhill across a sea of boulders, was ‘the scariest thing I have ever done off-road’; another, who had taken part in this year’s Trophée Cevenol (the legendary springtime randonnée, organised by the same company, which is well known as the toughest of the lot and regularly attracts entries from fully fledged challenge vehicles), said nothing in that event had been more extreme.

We already knew, of course, that the 1000 Rivières would be serving up a diet of serious rocks and extreme hairpins, with a liberal side order of scary drop-offs to go with the fantastic mountain scenery that’s everywhere you look. And we also knew that in an event where light weight and a short wheelbase are exactly what you want, a minimally modified Nissan Patrol five-door is, well, exactly what you don’t.

But that’s what we drive, as you’ll know from our Roadbooks every month (our reasoning being that if the Patrol can fit down the lanes we use, anything can). So here we were, having made a complete cock-up of a downhill hairpin, sat perpendicular to the track with our front bumper hanging over a sheer drop and our wheels spinning in reverse. Oh joy.

Thankfully, once engaged, the Patrol’s rear diff lock allowed us to ease it very carefully away from the edge and start manoeuvring it back into the position it would already have been in with a competent driver at the helm. A standard-fit item, the locker was infinitely preferable in this situation to the electronic traction control most manufacturers favour now, which need you to add throttle to make them work – ideal on carefully constructed test tracks at county showgrounds, but just what you don’t want in such a delicate real-world situation.

A little further on, I demonstrated that while my driving may have been crap, at least my navigation was crap too, when acting as a spotter for our team-mate Kit Kaberry and guiding one wheel of his 90 straight into a hole that very nearly added it to the day’s casualty list.

The two vehicles made an interesting contrast, with nearly two and a half feet between their wheelbases and rubberware which was standard-sized and only moderately aggressive. The 90 had mildly raised springs and shocks but no diff-locks, whereas the Patrol remains completely standard in terms of suspension and drivetrain alike.

As you’d imagine, the big difference between them was that Kit was able to tackle breakovers and tight corners with a lot less fuss, whereas we had more ultimate traction to make up for our extra weight. We’d aired our tyres down to about 22psi all round, whereas Kit kept his standard; truth to tell, we never once came to a situation where we could put our hands on our hearts and say that it made an appreciable amount of difference to proceedings.

Certainly not towards the end of day one, at any rate, when we emerged from a lengthy section of easy forest tracks, cut across a main road and followed the roadbook into another tract of tall pines, only to join a convoy of 4x4s waiting to tackle one of those made-by-a-forestry-wagon mud holes in the gathering dusk.

The guy in front of us, a Brit in a raised Disco with 35-inch tyres and front and rear ARBs, bruised his way through the mud and ruts without a problem. But more weight, less clearance and smaller tyres conspired against the Patrol, and when I completely forgot to engage the rear locker its fate was sealed.

Time for our brand new TDS winch from David Bowyer to lose its cherry, then. Mounted on an equally new ARB bumper, it did a good, no-fuss job despite being rigged for a hugely optimistic single line pull – we were right on the edge of what it was able to do without a snatch block, but soon we were rigging a kinetic rope to the Patrol’s other ARB bumper to haul out Kit, who had made it no further than us.

It was on the way to La Bastide Puylaurent for the overnight stop that we encountered that annihilated bridge, but the following day was to prove a lot more gentle. All things are relative, however; the morning’s daily briefing was full of assurances that today would be much easier, but it didn’t take long for the effects of those freak rains to make their presence felt. A massive pile of mud and rocks, the result of one of those landslips, had a bellied-out Grand Cherokee parked on top of it and a lot of people milling around paying scant attention to the fact that we were surrounded by some of the most fabulous scenery in all of Europe.

After an aborted attempt to drag the Jeep forward, we nosed the Patrol up behind it and winched it backwards for another try, dodging a gaggle of quad bikers who clearly didn’t think it was necessary to stop, or even slow down very much, just because they happened to be passing within about six inches of a tense winch rope (and, indeed, a tense winch man).

Finally, back where he started, the driver of the Grand Cherokee was presented with an alternative route round the crest he’d been stuck on, using another part of the rubble deposited by the landslip. It wasn’t going to ground anyone out, but it had to be driven with absolute precision… and if it wasn’t, you were going to fall off a sheer edge into a gorge. With one of his mates as a spotter, he inched it round, finally pulling back on to safe, solid ground as the downhill side of the soft, rubbly soil crumbled alarmingly away beneath his wheels.

At this point, with the even longer Patrol still to be wrestled over the crest, Steve and I looked at each other in a would-you-like-to-drive-now sort of way. Some time later, my innate politeness triumphed and he clambered into the driver’s seat – and, by the simple expedient of absolutely giving it death, launched the truck right over the crest and down the far side. Respect.

We’d already established that the whole it’s-easy-today thing was to be taken with a pinch of salt. But what followed was possibly the most concentrated spell of world class off-roading I have ever had the good fortune to experience. And I’ve experienced the Atlas Mountains, Great Sandy Desert and Rubicon Trail. On and on we went, picking our way along tracks incised into the huge valley sides with sensational views in every direction – you just wanted to roar with joy, it was so perfect. Now at least, we were in the zone.

And we stayed there for what seemed like hours. At times, the track became seriously boulder-strewn and we’d pick a hesitant path from axle-twister to axle-twister, once even positioning the Patrol so as to try and use one of its chassis rails as a rock slider. Then things would open out and we’d speed up to a gleeful 20-30mph, grateful to finally be enjoying the delights of high box for a while.

It was almost inevitable that the following day was going to be an anticlimax. It turned out to be anything but… at least, for those who tried it at all. During the night, the glorious weather we’d been enjoying broke with a vengeance, meaning those dry, grippy rocks were now unbelievably treacherous. And at the morning’s briefing, the organisers painted a daunting picture of what lay ahead. You could see people looking at each other as one warning after another came out, shaken by what they were hearing.

It was enough to convince most British entrants, ourselves included, that discretion was the better part of valour. It’s not that any part of the route was going to be impossible, but here and there the consequences of things going wrong could clearly be very damaging indeed. Perhaps it was because when you’re this far from home, you start getting windy about the fact that your vehicle still has to get you back to Blighty, but the locals were much more gung-ho and most did start the day.

Unlike most of the other Brits we spoke to, our 90 and Patrol had made it this far with nothing more than a few minor dents to add to the collection. Leaving them in the car park was gutting, but when we walked into some of the sections and watched what was going on, we knew we’d done the right thing. When you see one quad lowering another down a rock face on a tow rope, as in front of it a Land Cruiser gets winched sideways off the tree that’s holding it up and behind, a 90 is lashed to an anchor point to keep its front from running away while its crew try to change a trashed tyre, you know you’re getting towards the extreme end of the scale.

How much of this was down to the crazy weather, and how much was down to the organisers wanting to give people three days of off-roading they wouldn’t forget in a hurry, is a matter for debate. But one thing’s for sure. If you love off-roading, and lots of it, this is an event you’ll fall for hook, line and sinker. We left for home full of relief about having survived scot-free. Now, just days later, I just want to go back.