Same Difference

Ask any 4x4 builder and he’ll tell you that every good project starts with a good base vehicle. In the case of Matt Chinnick’s Suzuki, he started with a completely pristine original Santana, so he could hardly help but get it right. One set of Land Cruiser axles later, he was well on the way to getting it very right indeed…

Words Olly Sack

Pictures Steve Taylor

We’ve run a lot of stories down the years, about a lot of off-road fans and a lot of the trucks they’ve modified. And you probably know the formula. Buy an old shed, pull it apart, fix it up and turn it into a toy that ought to last a couple of years if you keep on top of the rot and damage.

Well, Matt Chinnick did it differently. A professional welder with a sideline in modding 4x4s, he starts the story as a man with exactly the right skills to build a truck worth looking at. The right skills and, indeed, a truck that certainly was worth looking at, though mainly because of what had just happened to it.

‘My first 4x4 was a Suzuki SJ410 Santana’, Matt explains. ‘That only ended up with basic mods before it got towed into a tree, which bent and snapped the chassis.’ What was it being towed by, you’ve got to wonder. Godzilla?

‘The second 4x4 had to be the same,’ Matt continues, ‘as I didn’t get a chance to play with the first one enough. So I found a lovely standard silver SJ410 Santana which was previously owned by only one person from new.’

Cutting up mint-condition vehicles is frowned upon in some circles. But would you sooner work on one that’s always been cosseted and looked after or one that’s been parked in damp weeds and taken out once a month for a pasting in sill-deep mud? Not a hard question to answer, is it?

So there we are with what must have been one of the last pristine Santanas in the UK, now lying in bits on Matt’s workshop floor. The largest bit was the chassis, which survived the whole process - albeit with a lot of modifications, most of which were put in place to facilitate the switch from the original leaf springs to coils.

All the old mounts had to be cut off, then new radius arm mounts and spring perches were welded on – with the axles’ positions moved further to the front and back at the same time. This allowed Matt to fit a set of Toyota Land Cruiser 80-Series axles, and you know they’re going to be about the strongest bit of the whole rig.

One consequence was that the Suzuki steering box now wouldn’t fit, so that too was replaced with a Land Cruiser 80 unit. But don’t worry, this isn’t going to be a simple transformation into a Land Cruiser.

There certainly wouldn’t have been room under the bonnet for a 4.2-litre straight-six, for example (as you’ve either already read or are about to, Dominic King had enough trouble getting a Land Rover TD5 to fit in his SJ), but Matt wasn’t satisfied with the stock SJ four-pot either. It wasn’t so much the horsepower that was the issue, it was the torque, or lack of it.

Like Dom, he turned to Peugeot and dropped in the French company’s 1.9 turbo-diesel, this one removed from a knackered old 405. Unlike Dom, he stuck with it.

Matt reports that it was a simple fit, except the inlet and exhaust manifolds had to be changed. And then the intercooler on the top didn’t suit him, as it turns out he hates bonnet bulges. ‘So the inlet was modified so that a front-mounted intercooler could be used,’ he explains. ‘My only problem was that my intercooler was too tall. So I cut it in half.

‘And the radiator was the only one I could find to fit in the gap, so that’s from a BMW E36 318i. As for power output – I haven’t a clue. The turbo and fuelling have been turned up a lot, so there’s lots of boost and lots of black smoke!’

Behind this, the gearbox is from an LDV Pilot van – not as bizarre as it sounds, since that also runs the Peugeot engine and so the box is a straight fit. The transfer case is a Rock Lobster, which effectively lowers the low gears and raises the high ones, hopefully balancing out some of the mathematical butchery achieved by running it on 35-inch tyres.

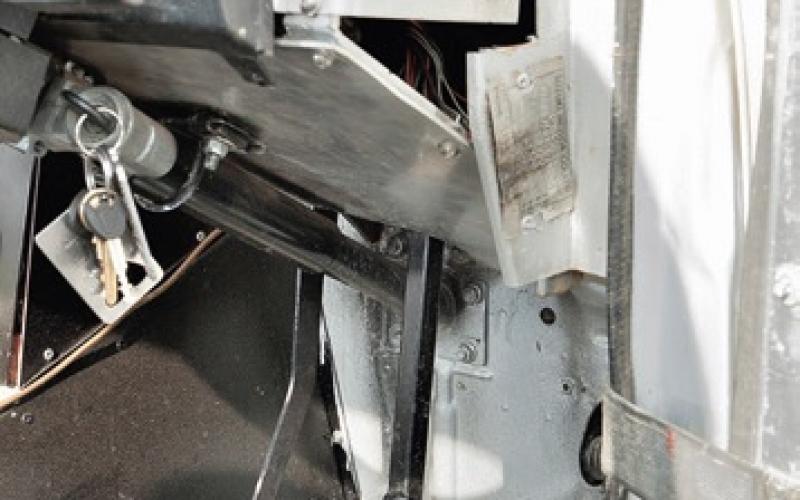

Both props are custom jobs, which they’d need to be to take account of the transfer box having Suzuki output flanges and the axles having Toyota inputs. The length of props required by all these mods is at odds with anything you could call standard, too. As for the shaft from the Peugeot gearbox to the Suzuki-based tranny, Matt takes up the story: ‘It’s custom-made and very small yet very clever! It’s half a Suzuki axle prop and half a Suzuki gearbox prop welded together with all the right flanges on. And it’s only 148mm long!’

The suspension displays the same level of slightly unusual thinking. At the front, Matt has fitted standard Land Cruiser springs. But then he fitted Vauxhall Carlton shocks, for some reason. At the back, he didn’t do the same again, oh no, he put on Hi-Lux springs teamed with Vauxhall Omega shocks. Who needs to spend a fortune on 16” coil-overs, anyway…?

The roll cage starts with a brace of rock sliders bolted to the chassis. These have two lengths of box welded to them so the cage can run between the inner and outer skins and start halfway up the body. Both front and back sections are mounted to both bumpers, so it’s very strong indeed – it would take a seriously heavy or freakish rollover to make it move.

As Matt says, this is a vehicle that was built not bought. But it still manages to look recognisably like a Suzuki, albeit one that’s been turned into a crew cab.

Bits that don’t look very Suzuki, on account of they’ve gone, include the inner arches and front grille. The later went south, along with the bodywork surrounding it, when Matt fitted the winch bumper he’d fabricated – along with a set of BMW E30 headlights, which have an orange ring of LEDs around them to act as indicators.

These are joined at the rear by Vitara lights mounted out of the way in the tailgate, and there are also some home-made spots. Home-made? Yes, as Matt explains, ‘from a simple piece of tube with 12W downlighters, giving both wide and narrow beam to light up the track best.’ Fiendishly simple and clever.

Unusually, Matt has simply fitted two cheap Chinese winches fore and aft. And he’s very happy with them: ‘Even though these are cheap, neither has ever let me down, and they’ve surpassed my expectations.’ Fair enough. The wiring powering the winches, lights and so on has caused Matt a ‘massive headache’, but he reckons he’s finally sorted it.

It took something like 14 relays to get him there, and they share the truck’s interior with a pair of seats from a Honda Prelude as well as Matt’s own design of parcel shelf. ‘I made it to go in the rear of the cab’, he explains proudly, ‘so it can house the speakers, and it’s a clever way to keep my socks dry when driving through deep water!’

These are the things that matter, of course. And when you’ve built yourself a vehicle this capable from nothing but, er, a completely pristine classic Suzuki, you’re entitled to allow yourself a few little luxuries. After all, some people may content themselves with nursing shed from playday to playday. But this SJ is a cut above.

Five Alive

When Dominic King bought an SJ with no engine, he knew what he had to do. Put an engine in it, obviously. So he… chopped up the body, built a cage, extended the chassis and gave it the heart and soul of a TD5 Land Rover

Words Olly Sack

Pictures Steve Taylor

There’s a lot of trayback Land Rovers in the world, and at first glance the truck Dominic King built a few years ago was one of them. But actually, what you’re looking at in these pictures is a Suzuki SJ.

It’s a Suzuki SJ with no shortage of Land Rover bits in it, admittedly. But precisely none of them are visible from the outside.

Dominic is an engineer by trade. So it won’t surprise you to hear that when he replaced the SJ’s original four-banger with a much more powerful TD5, it was for that classic engineer’s reason – as far as he was aware, no-one else ever had.

Actually, he didn’t replace the SJ’s original four-banger – because the SJ he bought didn’t have an engine in it. And even if it had have done, he wouldn’t have replaced it with a TD5 either – because the first thing he dropped in had an altogether less off-roady past behind it.

But Dom didn’t kick off with the engine, anyway. He started on the outside and worked his way in.

What he bought from a mate was a totally standard SJ (minus engine, of course). It was a hard-top with a full cab, so that was immediately chopped down to a truck cab as Dom was after building a hardcore off-roader.

One of his first jobs was to build a cage and rear tray. These went on to a chassis that was extended to 102” and then strengthened by pug-welding 5mm plate on to both sides all the way down. Given what was to come, it was probably sensible to build a chassis capable of taking more strain than the Suzuki engine could generate.

As we’ve hinted, the next thing that happened didn’t involve the engine the vehicle ended up with. People have been fitting Peugeot turbo-diesels in Suzukis for a long time and that’s the way Dom went, lobbing in a 1.9-litre unit from a Peugeot 306. In an unusual twist, he made the conversion plate himself – the man’s an engineer, lest we forget.

But there was a problem. The vehicle’s overall gearing was such that rather than turning the wheels, the much torquier diesel unit responded to being asked to move so much weight by simply spinning its clutch. Not much fun, and it smells bad.

The answer? A Land Rover TD5. ‘I had no plans, no measurements, and I didn’t even know if the engine would fit between the chassis rails!’ says Dominic. ‘But I had two choices. I could go for lower gears with more power, or change the engine.

‘Going from a 1.9-litre to a 2.5-litre engine was the only option. Like they say: there’s no substitute for cubic inches!’

One problem with more cubic inches is of course that they take up… more cubic inches. So to get it in, the bulkhead was opened up and the engine moved as far back as possible (which also helped with the vehicle’s balance)

It was so tight, in fact, that he had to remove the handbrake drum just to get the unit into place. It took him a week to get the brake servo sorted, as that too no longer had enough room as it stood. ‘Trust me,’ he says, ‘everything was just so tight!’

But he got it to fit, and now he could move on to the gearbox and transfer case. These too came from a TD5 Land Rover, as did the axles. Fitting the axles was, according to Dom: ‘really easy. It was just a few hours with a tape measure and some chalk!

‘I made up my own radius arms front and rear, as long as possible to eliminate axle tramp, and polybushed them. Then I got rid of the standard A-frame rear axle set-up. On the front I strengthened the shafts and CVs and fitted an adjustable panhard rod and my own diff guard. On the back axle I also fitted strengthened shafts and my own panhard rod and diff guard, as well as an ARB Air-Locker.’

So, we’ve got axles and a car. Springs, we need springs.

‘I had all the power I needed,’ says Dom. ‘But now I had to get some good suspension. The only way was coil-overs and, with my name being King, the choice was easy!

‘I believe in the maxim “buy good, buy once.” On the front, I fitted 16-inch King coil-overs, with 14-inch coil-overs on the rear. And what a transformation! The ride was so stable, even with all the lift it had, and it handled corners better than I imagined. Off-road it had more flex than Arnold Schwarzenegger at Mr Olympia! I was very happy!’

On the ends of the axles, he fitted a set of 35x10.50R15 Fedima Siroccos. These are brilliant tyres because they’re strong, very aggressive, cheap to buy (for something so specialised) and because even though it says 35” on the casing, with the depth of their tread when they’re new they stand closer to 37” tall.

He fitted them using home-made beadlockers, which is something most of us can’t do. Not before breaking a tyre off its rim while off-roading on low pressures, which is something any of us can do. Anyway, for prolonged road use he also owns a set of 33” mud-terrains on black Silverline five-spokes, which saves unnecessary wear on the Siroccos and helps retain at least a bit of civility in the cab.

Brakes are all Land Rover standard, although there’s a hydraulic handbrake to replace that original drum unit that was pushed aside in all the squeezing. Similarly, the PAS box started life on a TD5. But in terms of Land Rover (or indeed Suzuki), that’s about it.

The body is of course home-made. ‘I made it up as I went along,’ admits Dom. ‘The front wings just would not work at all, so I made the complete front end from scratch. The wings were actually formed round the tyres. I also made the rock sliders and welded them into the sills. I then made all the bumpers from scratch, although I’ll admit I did change them a few times!’

Inside all that bodywork, the interior features a leather driver’s seat from a Citroen BX. Nice. The passenger seat? Rather mysteriously, Dom just says: ‘I found the passenger seat in me mate’s van.’ Let’s hope his mate wasn’t sitting on it at the time.

There’s also a big box of spares in the back, and the ECU is up under the dash in a sealed, breathable box since clearly there’s a worry about water. Electricity is supplied by two Odyssey batteries with a remote fuse box for all the various add-ons.

These include the two winches. On the front is a Warn 8274 featuring Dom’s own top housing and fairlead, while the rear is a Warn M9000 with again his own fairlead. Both run Albright solenoids, which in some situations is like saying both run.

Dom also made the fuel tank, which carries a whopping 120 litres. Maybe at that point he was thinking about putting in a Chevy V8 rather than the TD5…

Not that he had much of a chance to test its long-range capabilities first time he used it in competition. ‘We broke a few things, but, like a bad penny, we wouldn’t go away! Just in one section we knocked a tyre off the rim, then broke a front CV, and then broke a rear halfshaft!’

He had his best competitive times with his co-driver Chris Hunton and his mate Patrick Smart, who also helped with the wiring and build. There’s no question that they put together a competitive vehicle that blends in at first glance but, the more you look at it, stands out more and more from the crowd.

‘What we made was surprisingly fast!’ remembers Dom. ‘We remapped the ECU, put on an aftermarket fuel pump and turbo and tweaked some stuff. We reckon power was about 180bhp, but even with 120 litres of fuel on board the whole thing only weighed 1540kg, so the power to weight ratio was really good.’

Combine that with great handling, ground-hugging flexibility and lots of traction, and you have a complete Challenge vehicle. It’s not a complete Suzuki, or a complete Land Rover, but you’re looking at the best of both worlds here – and it’s a truck which went on to inspire many others.

![1, 2] The whole front end is made of tube, and beneath the bonnet there’s a plumbing job to be proud of – largely because the engine was designed with a top-mounted intercooler and, as you see here, Matt wanted to move it to the front. As you’d expect given Matt’s profession, the welding is impeccable](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-1-1.jpg)

![1, 2] The whole front end is made of tube, and beneath the bonnet there’s a plumbing job to be proud of – largely because the engine was designed with a top-mounted intercooler and, as you see here, Matt wanted to move it to the front. As you’d expect given Matt’s profession, the welding is impeccable](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-1-2.jpg)

![4] BMW once again provided an important element, in this case the headlights. Note the LED rim is actually an indicator – would it be corny to describe this as being a bit flash?](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-1-4.jpg)

![1, 2] Using axles from an 80-Series Land Cruiser means a lot of things. One is that<br />

they’re plenty strong enough, and another is that they contain locking diffs as standard.<br />

Here at the front, the axle went on complete with Land Cruiser springs and PAS box, though the appearance of shocks from a Vauxhall Carlton might come as a bit of a… well, shock](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-531.jpg)

![1, 2] Using axles from an 80-Series Land Cruiser means a lot of things. One is that they’re plenty strong enough, and another is that they contain locking diffs as standard. Here at the front, the axle went on complete with Land Cruiser springs and PAS box, though the appearance of shocks from a Vauxhall Carlton might come as a bit of a… well, shock](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-526.jpg)

![3] Compare this Plastimo fuel tank to Dom King’s fabbed affair, as found in the next article to this, and you’ll see two different solutions to the same problem. Both provide plenty of range and, crucially, live in new locations where they’re not going to become the weakest link in terms of ground clearance](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-534.jpg)

![2] Copper fuel lines run through the cabin where they’re safely out of harm’s way. The seats, whose leading edges you can just see here, are from a Honda Prelude](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-537.jpg)

![1] Matt’s skills are evident everywhere you look on the vehicle, but never more than here – where drive is taken from the gearbox to the transfer case via a propshaft that’s less than six inches long](/assets/Uploads/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-5.jpg)

![1] You can’t fit a quart into a pint pot, but you can fit a TD5 engine into a Suzuki. Well, you can if you carve open the bulkhead and consign the handbrake drum to history. Positioning the brake servo took a week on its own](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-543.jpg)

![2] First time Dominic took part in a challenge event, he fetched a tyre off its rim. So he went home and went into the workshop, and before long he’d made up a set of beadlockers to keep his 35” Fedima Siroccos clamped tightly to their eight-spoke wheels](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-541.jpg)

![3] Not many challenge trucks have the capacity to carry 120 litres of diesel, but for some reason that’s the size of the tank Dom fabricated. This thing could probably have done King of the Hammers without ever having to stop for a fill-up](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-545.jpg)

![4] Two winches mean two Odyssey Yellow- Tops, which also look after a set of X-Lites, Wipac headlamps, work lights and NAS-spec rears – as well of course as the small matter of the alternator and so on](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-542.jpg)

![2, 3, 4] When you’re fitting a big engine into a small engine bay, being able to rebuild the<br />

entire front of the vehicle around it is quite a luxury. People who put V8s in Minis and so on<br />

would be jealous of Dom here, though they might not envy him the amount of hard labour<br />

it took to fabricate the wings and front winch mount. It won’t have escaped your notice that<br />

the winch living in it doesn’t have a rope; this was a one-off state of affairs which happened<br />

to coincide with our photoshoot, which wasn’t so great for us but from Dom’s point of view<br />

must have been infi nitely preferable to him turning up to a challenge event in that state.<br />

The winch itself is a Warn 8274 with a twin-top conversion](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-553.jpg)

![2, 3, 4] When you’re fitting a big engine into a small engine bay, being able to rebuild the<br />

entire front of the vehicle around it is quite a luxury. People who put V8s in Minis and so on<br />

would be jealous of Dom here, though they might not envy him the amount of hard labour<br />

it took to fabricate the wings and front winch mount. It won’t have escaped your notice that<br />

the winch living in it doesn’t have a rope; this was a one-off state of affairs which happened<br />

to coincide with our photoshoot, which wasn’t so great for us but from Dom’s point of view<br />

must have been infi nitely preferable to him turning up to a challenge event in that state.<br />

The winch itself is a Warn 8274 with a twin-top conversion](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-554.jpg)

![2, 3, 4] When you’re fitting a big engine into a small engine bay, being able to rebuild the<br />

entire front of the vehicle around it is quite a luxury. People who put V8s in Minis and so on<br />

would be jealous of Dom here, though they might not envy him the amount of hard labour<br />

it took to fabricate the wings and front winch mount. It won’t have escaped your notice that<br />

the winch living in it doesn’t have a rope; this was a one-off state of affairs which happened<br />

to coincide with our photoshoot, which wasn’t so great for us but from Dom’s point of view<br />

must have been infi nitely preferable to him turning up to a challenge event in that state.<br />

The winch itself is a Warn 8274 with a twin-top conversion](/assets/bulkUpload/_resampled/CroppedImage800500-556.jpg)