The Last Post

As the new Grand Cherokee prepares to make its UK debut, we took one of the last examples of the old model to explore the abandoned forts of north-east France. A fitting send off for a vehicle that traces its history back to the bloody past of this very region

On 19 July 1870, King Napoleon III of France declared war on Prussia. It was to prove one of the most disastrous political moves of modern times, plunging an unprepared and ill-equipped army into an unwinnable conflict against a far superior enemy.

It took a mere six weeks for Napoleon to capitulate. But far from being over, France’s troubles were merely beginning. Following an armistice agreement that saw it pay five billion francs in reparations and give up Alsace and much of Lorraine, the country emerged to find that the geography of its north-eastern frontier had changed – in a way which, should hostilities break out once more, would provide the Prussians with a direct route towards Paris.

The French capital had played a pivotal role in the war, with the proclamation of the famous Commune and its subsequent quelling a year later during Bloody Week when more than 25,000 of the city’s residents were massacred by troops loyal to the government of Adolphe Thiers. The armistice had only been secured after a lengthy Prussian siege and bombardment of the city, and France’s conquerors wanted to be sure they would have unfettered access in future conflicts.

But the new government had other ideas, and quickly drew up plans to defend its biggest prize. What it came up with was a spectacular, hugely ambitious scheme that would pepper the landscape with a massive network of forts, the forerunner of the even more extraordinary Maginot Line.

Masterminded by general Raymond-Adolphe Séré de Rivières, these forts turned out to be obsolete even before they were complete. Yet they were still in action by the time not one but two German invasions had ridden roughshod over them. And when D-Day came, almost three-quarters of a century after their commission, they were among the first military emplacements on mainland Europe to throw their arms open to the first Jeeps.

Half a century later, many of these forts played host to celebrations and acts of remembrance to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Europe’s liberation from the Nazis. Of the hundreds that were built, most remain more or less intact – locked up and long-since abandoned, of course, but maintaining their own silent vigil for those who fought and died within their austere stone walls during two world wars.

Not that Séré de Rivières, nor indeed anyone else involved in the project to defend France against Prussian imperialism, could ever have imagined the sort of changes that would take place in the century following the forts’ construction. Almost unbelievably, they were designed with ramparts made of nothing more substantial than earth, yet they were still in use during an era of jet aircraft and nuclear weapons, and were only abandoned on the cusp of man’s first ventures into space.

So it was with the Jeeps that plied the tracks from one fort to another, and indeed in some cases the tracks themselves. Following Operation Overlord, the original Willys MB was a familiar sight around the entire region of north-east France. Now, 50 years on, here we are exploring them from the almost unfeasible comfort of a Grand Cherokee 4.7 V8 Overland.

Of course, even this technological marvel is showing the ravages of time. It’s an off-roader in an era of soft-roaders, and many observers of the 4x4 market think that makes it yesterday’s news. Hard not to agree, however reluctantly, when its replacement is already on sale in America and due in Britain in a matter of months.

But the Grand Cherokee is nothing if not a proper old trooper. Where others flatter to impress with their electronics and tarmac niceties, it sits you on top of all the right stuff. It might not be about conquering countries anymore, but it certainly knows how to conquer it some countryside.

And it’s not exactly a trial on the autoroute for all that, least of all in Overland form and certainly not with that 4.7-litre High Output engine up front. Punching your way into France is a lot easier without a million machine-gun-toting Germans trying to stop you, of course, but 255bhp and 314lb.ft make it more of a breeze than ever. Just so long as you make regular stops to slake its 17.1mpg thirst.

The section of Séré de Rivières’ fortifications we were heading for was in the Val de Meuse, between the towns of Commercy and Toul – a short Panzer ride from the German border, and an area of tremendous strategic importance given its position on the confluence of three major rivers. A little way to the north-west is Verdun, site of some of the worst horrors of World War I; beyond that, on the border with Luxembourg, is Longwy, where the breach in France’s German border following the 1871 armistice began.

Séré de Rivières’ strategy was to create two defensive ‘curtains’, each made up of a series of impregnable forts with overwhelming firepower. Between the curtains was an open area into which invading forces would be channelled, allowing the French army to isolate them and finish them off. Decades later, the same tactical naivety was to render the Maginot line useless when the invading Germans simply went round the side. But what embarrassed the defenders of Paris on this occasion wasn’t the location of their mighty fortifications, but the fact that their fortifications turned out not to be that mighty after all.

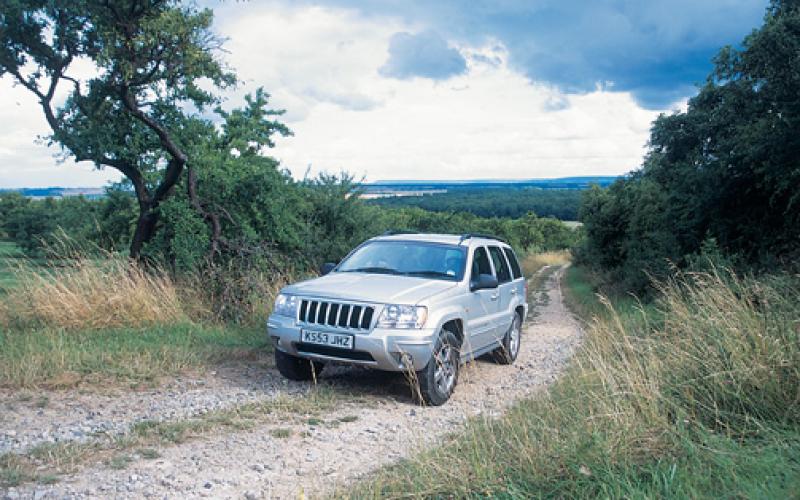

Pointing the Jeep north on a smooth gravel track leading into the hills overlooking Vertuzey, we followed wooden signs taking us along a bumpy field edge towards the Fort de Gironville. The Grand Cherokee’s live axles proved their worth every step of the way here, keeping us out of danger in ruts and easing their way in and out of potholes left by heavier vehicles in wetter times.

We navigated our way around a section through trees whose branches would have left their marks on the Jeep’s expensive metallic paintwork, finding our way back to the track and fetching up outside the fort’s quietly decaying ramparts, now shaded by tall deciduous trees and slowly being reclaimed by nature.

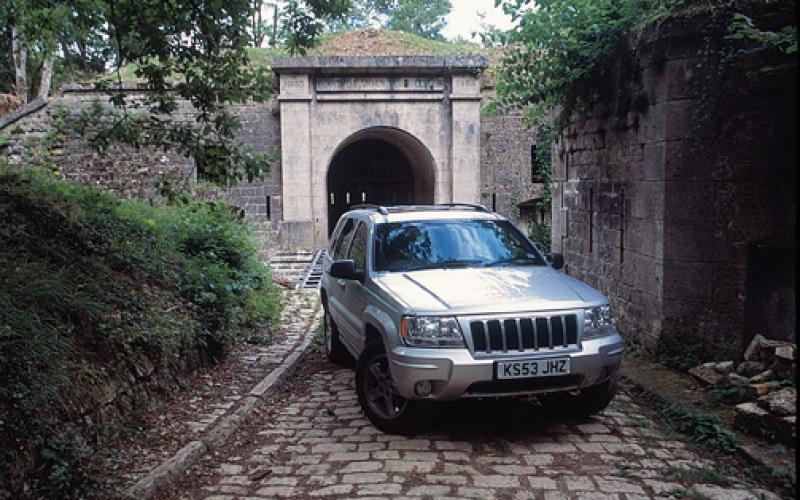

This is how many of these forts and emplacements have ended up, destroyed by time rather than warfare. Amid the wholesale carnage of two world wars, many of them remained intact. Gironville is a perfect example: abandoned but not ruined, we found it resting quietly in the dappled sunlight at the end of our field-side track. There’s a car park of sorts, but no ticket booth, no souvenir shop, no multi-lingual tourist information plaques, no barriers telling you where you can and can’t go. There is no Fort de Gironville Experience.

And in many ways, that is the experience. As a Brit, you’re used to heritage being packaged, presented, explained and, of course, commercialised to death. You’re not used to it simply being there. We refrained from backing the Grand Cherokee too far into the ramparts for photographs, not because we thought anyone would stop us but because, well, it just felt wrong.

Further along the same set of tracks, an opening in the trees to one side leads to the Fort de Jouy Sous-les-Côtes. Unlike Gironville, this is closed up, perhaps to stop local kids from using it as a playground, but it’s still almost completely intact. Even the bridge leading across what appears for all the world to be a moat looked like it would happily bear the weight of the Grand Cherokee. Not that we tried, for obvious reasons.

Jouy is a perfect example of what turned out to be the big flaw in Séré de Rivières’ plans. Despite having spent billions of francs on the project, the French generals had failed to make their fortifications future-proof. Jouy, and other forts like it, were designed to withstand an enemy onslaught – but only using the weapons of the day.

Fundamentally, the new forts protected their artillery behind nothing more sturdy than walls of soil. Their structures were partially buried, but of course their gun emplacements had to be exposed – and this problem became much more acute in 1885 when Eugene Turpin invented melinite. Suddenly, explosives were 25 times more powerful – and the walls of earth surrounding Séré de Rivières’ ‘impregnable’ line of defence were looking like its Achilles’ heel.

Just as the Grand Cherokee has constantly evolved to keep pace with ever-stronger rivals, France’s military planners responded with a massive programme of modernisations to save their bank-breaking line of defence from turning into an instant relic.

Yet it wasn’t until 1897, two years after Séré de Rivières’ death, that work began. An indication, perhaps, of the fear inspired by a general who had been instrumental in placing the blame for the shambles of 1870 on Marshal Francois-Achille Bazaine and crushing the revolutionaries in Paris following the proclamation of the commune. Modernisations to the 166 forts, 43 small emplacements and 250-plus gun batteries that had been built includes the addition of cast-iron turrets to some and the construction of concrete shells on others. The latter was used particularly on the German border.

It was all to no avail. By the time France’s fortifications were called upon to defend it against invasion from the east, the world had once again left them behind. Forts built to withstand columns of slow-moving foot soldiers, cavalry on horseback and primitive artillery found themselves pitched into a war of tanks, shells and mustard gas. The trenches of the Great War will soon be a century away, but even in those dark times the bodged fortifications Séré de Rivières left as his legacy looked like little more than a quaint anachronism. Which is, of course, why Gironville, Jouy and the rest are now mouldering relics rather than annihilated piles of broken stone.

In Britain, all these buildings would have been bought up and turned into luxury apartments for commuters. Another kind of annihilation, possibly. But in the shadow of Jouy’s imposing main gate, the nearest we got to urban living was when a Mitsubishi Pajero trundled past and pulled to a halt, and two French green laners got out for a chat. The Overland definitely met with their approval, until I told them how many euros I’d poured down its throat getting us even this short distance into their country.

Beyond Gironville, a rocky track full of axle twisters leads to a quiet crossroads on which stands the Fort de Liouville. This is only accessible in groups, though again there’s nothing commercial about the volunteers who show visitors around in their twos and threes. The quiet, bucolic feel of the area is in such clashing contrast to the thunder of the guns that have roared out so many times in its history, something that’s brought home as you descend through picturesque woods to the Etang de Ronval,

a quaint little lake on that locals fish patiently for brown trout. Rejoining the tarmac towards Marbotte, you almost immediately come upon a military cemetery where the French tricolour flutters over a sea of simple white crosses.

And if any further reminder of the price so many early Jeep drivers paid for the follies of 20th century politicians was necessary, one need only turn north towards the Butte de Montsec. Overlooking the Lac de Medine, this is a graceful, symmetrical hilltop on which stands a monument to the US troops killed in World War I. One of 25 such tributes maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission, Montsec is a classic colonnade approached from the car park via a long, open stairway. From within it, you can actually see the marks left on the plains below by the trenches.

As we travelled back towards Reims, the elegant, cosmopolitan capital of the Champagne region in which we were based, the day’s watery sunshine gave way and the sky turned the colour of ink as a massive thunderstorm gathered its forces for an assault on the plains around Verdun. Never being averse to a bit of sledgehammer symbolism, I imagined the storm that engulfed this whole area from 1914 to 1918.

However sanctimonious it must sound from the pampered existence of a comfortable 21st century, middle-class life, it doesn’t half send a chill up your spine to think, as you drive through the quiet countryside on holiday, there’s a very good chance that, at any given moment, you’re passing right over the exact point at which someone’s life was snuffed out in the ugliest circumstances imaginable.

War gave us marvels like the Jeep, as well as hastening the dawn of jet travel and encouraging many other technological advances which have brought countless benefits in peacetime. In many ways, the landscape of modern life has been shaped by the horrors of the past – and there are few places where the physical landscape bears more profound marks of war than in the north-east of France.

The trenches may be gone, but the scars still remain. And however many years pass, names like Verdun will forever summon memories of a dark chapter in the history of Europe.

For that reason, though they lie abandoned, forts like Jouy, Gironville and many others will never be allowed to crumble away. And neither will the most famous vehicle to be borne on the winds of war… It may be the last post for the Grand Cherokee as we once knew it, but this has been a vehicle that played its part in keeping Jeep’s heritage alive and well all the way into its seventieth decade.

The Way To Travel

We crossed the Channel en route to France with P&O, whose ferries are the good old-fashioned way to make the hop to Europe. They’re also a good deal cheaper than some of the alternatives (in fact, all of them), meaning you can do what we did and put your feet up in the Club Lounge, and still have enough left over for your first few tanks of fuel.

The other great thing about doing it this way is that it turns a chore into an adventure. Oh, and they’re pretty chilled at the terminal if you arrive a bit too late for the crossing you’re booked on, so you don’t need to fear you’ll get stung for an extra wedge just because one lorry tried to overtake another back on the M25 and your journey time grew by 25 minutes as a result.

The only drawback is that you have to drive through Dover to get to the port. But at least that way, you really do want to leave Britain by the time you drive up the ramp and into your ferry.

One handy tip if you’re heading to Dover on the M20, though. When the traffic gets snarled up, it gets really snarled up. If you don’t want to risk being trapped for hours, leave the dual carriageway at the second junction after the tunnel overlooking Folkestone and follow the old A-road to Dover, watching for the speed cameras. It takes a few minutes longer on a good day and about four hours less on a bad one.

See, that’s the sort of stuff you don’t read about on www.poferries.co.uk.

But everything else you need is there… If you’re heading for France this summer, make it your first (ahem) port of call.