Strip Show

John Docherty has had a lot of vehicles. And he’s stripped down and rebuilt almost all of them. No surprises for guessing what he did with his Suzuki Santana, then… although as it turned out, that was just the beginning.

Of the very many off-road projects that are started around the world every year, the proportion of them that end up being written off as abandoned, unfinished or just plain scrap is enough to put anyone off. John Docherty’s Suzuki Santana is among them, at least in a manner of speaking – though you wouldn’t think so to look at it today. That’s because he had it more or less finished… before deciding that he’d got it all wrong and starting again from scratch.

An IT student from Glasgow, John has been doing stuff with cars since he was 15. He started doing maintenance on his dad’s car, and ‘it kind of snowballed from there.’ His dad bought him a MIG welder and encouraged him to learn how to use it, and at the age of 19 he restored a Capri 3.0 Ghia from the ground up. ‘I was cheeky enough to knock on the doors of a few small body repair shops and offer to work for nothing on days off to learn skills,’ he recalls, ‘and working as a fitter for my dad gave me an excellent basis in engineering.’

Various accident-damaged restos followed, including a project to turn a Sierra Estate into a pick-up. ‘It looked better than sounds! It had a bit of a Aussie Falcon ute look about it, with a three-door Cosworth front and other go-faster bits.’

Finally, having helped a friend install a 300Tdi in an old airhead 90, he was ready to graduate to 4x4s. First came a Nissan D21 pick-up, which he pulled out of a field for £200 then stripped down and rebuilt. ‘I welded the bodywork and chassis and did the clutch, then spaced the body by two inches and raised the suspension by an inch. It looked fantastic – but it was terrible off-road!

‘Next, I managed to get a Land Rover 90 which again I stripped down and rebuilt – if you look closely, you can see a repetitive problem here! I gave it a two-inch lift, Polybushed the suspension and used stainless bolts everywhere, with an excellent second-hand chassis from Frogs Island and a fantastic second hand winch from David Bowyer. I put in an Isuzu 2.8-litre turbo-diesel engine, which was well worth doing, and finally a slide-and-tilt sunroof from a Renault Clio, which was even more well worth doing!’

The 90 saw a bit of action, but then one day its winch was put to rather an unusual use. John had heard about American Suzuki enthusiasts putting V6 engines in SJs, and figured that the combination of light weight and low-down torque would suit his driving style. ‘I always remember saying whenever I owned a Ford with a V6 engine that I could put a plough on the back and plough a field with it,’ he says.

So when a one-owner, low-mileage Santana came up at the princely sum of zero, he was right in there. ‘It was in a sorry state with most of a garden DIY project around it, two large dogs and a cat living in it and pretty much all of the bodywork needing attention,’ he says. ‘I don’t think the original owner had ever taken it off-road at all, as they thought they were going to have to clear the rubble and sand out of the way so we could drag it to the driveway. I told them not to worry, went and got my Land Rover and pulled it over the lot, much to their astonishment…’

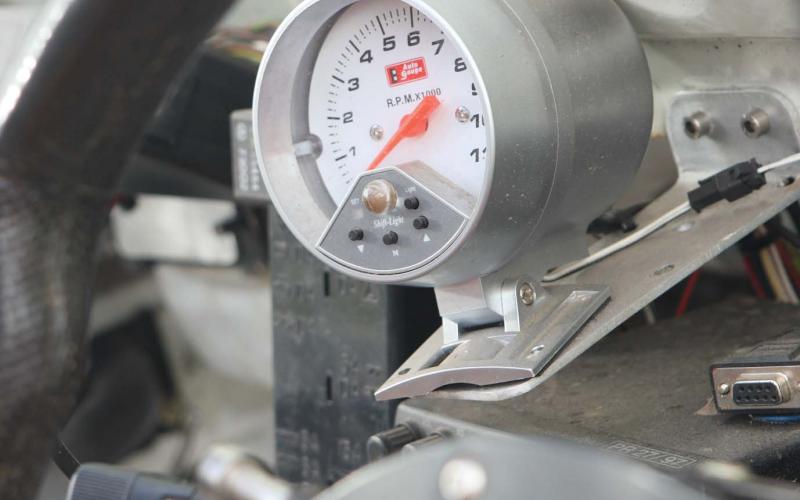

That was in January 2004, and the vehicle’s next stop was a patch of land belonging to John’s friend Jim Gorman. ‘Shockingly, I felt compelled to strip down the Suzuki and rebuild it. Jim owns a body shop in Glasgow, and he let me use an area of his yard to work on the vehicle. I wanted to get it finished quickly and get out there off-roading, and surprisingly it began quite well.’ Out came the Suzuki engine and in went a 2.8-litre Ford Granada V6 with a standard Ford C3 auto box linked to a B&M shifter, and by the start of summer he was ready to give it its first test drive.

This is of course a great day in the life of any project, except in this case it turned out to be a bit of a damp squib. ‘It didn’t feel right. Don’t ask me exactly what it was, but it was too heavy up front, the back was too light and the near-stock suspension wasn’t right. The only thing I was happy about was the automatic and the power the engine gave, as it was how I imagined it would be. But the vehicle just wasn’t balanced right – so it was back to the drawing board, with a mission to shed weight and redistribute what I couldn’t get rid of.’

This was the point at which the project could very easily have become one of the unfinished variety. As far as John was concerned, though, it’s only now that it really started. ‘I look back at that initial first completion of the car as a prototype that showed good and bad points,’ he says now. ‘I took a break from the project and got other things done, like getting my Land Rover tided up and beginning my current studies at college.

‘This proved to be good sense, as one of the things I was taught is development processes from analysis to implementation. It does help to organise what you want from the vehicle, organising jobs and ideas and keeping your end result to some sort of spec without going off on a tangent or blowing it out of proportion -– and I’m sure a few of us have been there, and in most cases ended with an unfinished project for sale!

‘Around a year later, I started again. So after salivating through analysis, screaming through design, sliding down the slippery slope of implementation and totally ignoring documentation, I’m now tearfully going through maintenance…’

You’ll have guessed by now that when John restarted the project, he did it from scratch. The Santana’s chassis remained fundamentally unchanged, but as well as adding all the brackets he needed for a repositioned engine and transmission, new suspension mounts and an aluminium fuel tank he found on eBay, which now lives above the rear axle, he also axed off any fixtures that were no longer necessary.

Up top, he based the build around a home-made cage which mounts to the chassis at the back and the scuttle panel at the front. This, he admits, is a bit of a half measure: ‘I should have brought it down to chassis, but it was a lot of hassle – and it’s stronger than the windscreen would have been on its own.’

Home-made bumpers provide further protection, but John has an interesting point of view when it comes to looking after a vehicle whose body panels he restored back from the rusted-out condition he found them in. ‘I haven’t had much damage off-road. Maybe that’s because it’s lighter and doesn’t put too much pressure on the sill panels, or maybe because more torque at slower speeds means I can take my time. The only thing that’s made me not go nuts with protection is the increase in weight it would mean. I’ve contemplated rock sliders and so on made from carbon fibre, but haven’t been able to find a laminator in the area yet. Also, I would like to copy the body panels in fibreglass as this tends to flex rather than dent.’ Talking of sills, the fuel lines are run inside them for protection, which says something about John’s confidence in the standard items’ ability to roll with the punches.

Underneath, a set of 235/75R15 Kumhos (‘big tyres are heavy,’ says John, ‘and I don’t want them’) dress the original Santana axles. ‘I was going to use Toyota Land Cruiser axles,’ he explains, ‘but changed my mind when I thought about the hassle and additional unsprung weight. I’ve been warned about Suzuki halfshafts being too weak to use with higher-power engines, but I haven’t found any problem. This may be down to the vehicle’s low weight and smoother automatic box. If I do have any problems I’ll probably keep the standard axle but change to hardened shafts and a rear diff lock rather than going to a heavier unit.’

While the axles themselves aren’t being difficult, the rear unit is showing a tendency to wrap under power in two-wheel drive. ‘The increase in torque tends to twist the rear springs, which puts the UJs at a strange angle and means they’re kind of fighting each other, with a lovely rumbling vibration at times.’ Nothing an anti-wrap bar shouldn’t fix, but all part of a vehicle’s development.

John’s diligent approach to the build should be enough to impress anyone, as should his willingness to mix and match parts from different vehicles to create a vehicle that does what he wants without having blown his budget out of the water. ‘It would have been great to have a bigger budget,’ he admits, ‘as I would have converted to coil-over suspension or spent more money on manufactured items instead of making my own – although I found this both interesting and fun. Most of the parts are based on normal everyday car parts, chosen either because I’ve worked with them before and know they would work better than originals, or because they were cheap and I could modify them to do what I wanted.’ Add in a heavily reworked electrical system designed to keep the effects of water at bay, a flip-front body allowing the heavy inner wings to go in the skip and a snorkel made from a bit of scrap flue he scored off the man who came to fix his fiancée’s boiler, and you’ve got a perfect example of ingenious making-do. There’s nothing unnecessary here, either: roof lamps, he reckons, ‘tend to light up the bonnet fantastically but nothing else, so I didn’t bother.’

Similarly, while he does have ‘tons of ideas’ for the future, he’s not about to do anything drastic in the way of fixing what ain’t broke. In particular, he won’t be turning his back on the low-weight philosophy that’s helped him make a well sorted off-road performer from what started as a nastily unbalanced prototype.

If you hadn’t got the idea by now, John’s a great example of an everyday off-roading fan who’s taken a bit of time to learn what he’s doing and thinks about his vehicle before wading in with the gas torch and angle grinder. A man worth listening to, clearly – so if you’re starting out in the 4x4 game, pay attention: ‘I enjoy the freedom and ease of off-roading with smaller groups rather than clubs, because as the sport is getting bigger the crowds are too, so you tend to trip over each other. But I do preach to people when getting into a sport like off-roading that it’s best to begin in a club environment. It’s the best way to learn driving and recovery techniques, as well as how to use winches and other equipment safely.’

He might also have added that the best way to learn about building a vehicle is to get in there and just do it. Because that’s what he did, not once but twice – and he’s got himself a really nifty grass-roots off-road machine as a result. Not bad for an abandoned project…

FORD GRANADA V6 ENGINE CONVERSION, DIY PANHARD ROD, B&M SHIFTER, SJ