Unfinished Symphony

Paul Ruddick has been building his SJ413 for ten years, but he still says it’s not finished. There’s more to it, though, than most vehicles achieve in a lifetime.

Ten years ago, Paul Ruddick bought a Suzuki SJ413. No big deal, lots of people have done that – including Paul himself, actually, who’d already owned a couple of SJ410s by this stage in his life, modding them as you do and having fun in them at playdays and on green lanes.

A feature of his early off-road toys was that he tended to use them, kill them and replace them. But having done enough of that, he was ready to start developing a truck worth keeping. He started, very wisely, with a roll cage, hiring a bender and buying a batch of tube then setting to over the course of a weekend. Working with his boss (not something you hear all the time), he made a set of rock sliders which also acted as mounting platforms for the front and rear hoops of a six-point exo structure.

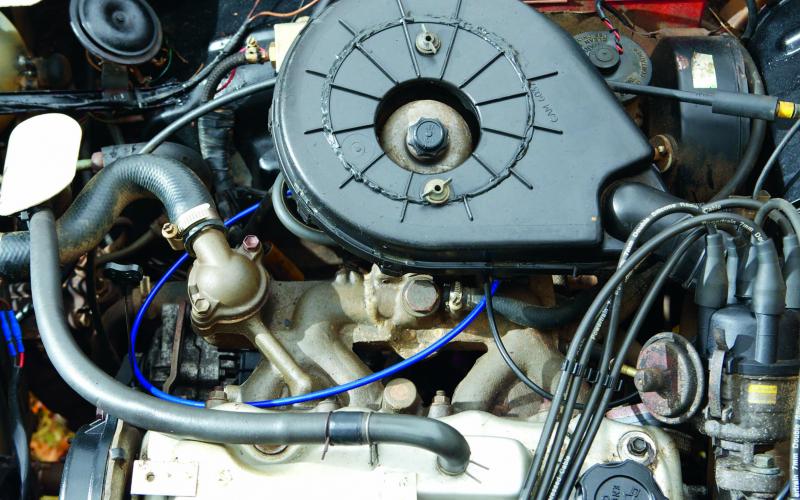

As the build went on, he dropped in an 8-valve 1.6 engine from a Suzuki Vitara, which he mated to the original gearbox using a Muddy Zook adapter. This breathed in through an Austin Metro carb and air box, the latter modified to keep water at bay, and was cooled by a higher-capacity rad from a 16-valve Vitara.

The SJ was already coming along very nicely, aided by a prototype KAM diff-lock in the back axle, and Paul was pondering on the idea of upgrading the suspension using leaf springs from a Jeep Wrangler YJ. But then he was offered the chance to buy a Samurai – with 3-link coil-sprung suspension and ARBs in both axles. A big step forward, surely?

Yes… and no. The coiler was, in Paul’s words, ‘80% finished.’ When you see a car like that up for sale, all too often it’s because someone’s started it with great intentions and got a long way down the road before realising how much they’ve done wrong, and maybe that was the case here. Either way, Paul got Richard Wattam to take a look at it, and that really is not what you need to see happening if you’re trying to sell a car whose suspension doesn’t move properly.

Sure enough, Richard was concerned by the amount of axle-steer going on under the Suzuki. The price was right, though, so Paul bought it anyway… and stripped it for parts.

Among these was a set of Fox coil-overs, which Richard coveted but Paul now owned. Paul coveted something too, though, which was Richard’s know-how with suspension geometry, and if you can’t work out where this is going, you need a strong coffee already.

And so a plan was hatched. Paul would take his still leaf-sprung Suzuki to a playday at Kirton Off Road Centre, which is just a few miles south of where Richard’s based. He’d head home with an empty trailer and a couple of months later, he’d be the owner of a coil-sprung SJ413 with a three-link system to be proud of, not scared of.

And that’s exactly how it turned out. Paul is no slouch in the workshop himself, and there’s no a lot that he hasn’t turned his hand to, but he knows when to leave it to the masters of the art. And he’s generous in his praise of Richard’s skills, both at the design stage and on the coal face.

‘I didn’t want to do something that would make the car worse than it was,’ he says. ‘I’d fallen out of love with it because of the way it rode on the leaf springs. The choice was to coil it, or buy a Land Rover instead. Richard worked out all the dimensions so that the three-link system would work properly. I just supplied him with a set of shocks and springs, and everything else he manufactured himself from raw materials.’

Those springs were 14” Rally Design coils, rated at 225lb all round, while the shocks were Rough Country units with 14” of travel up front and 16” at the back. He reckons the whole lot cost about £330: ‘Cheaper than buying a good set of leaf springs!’

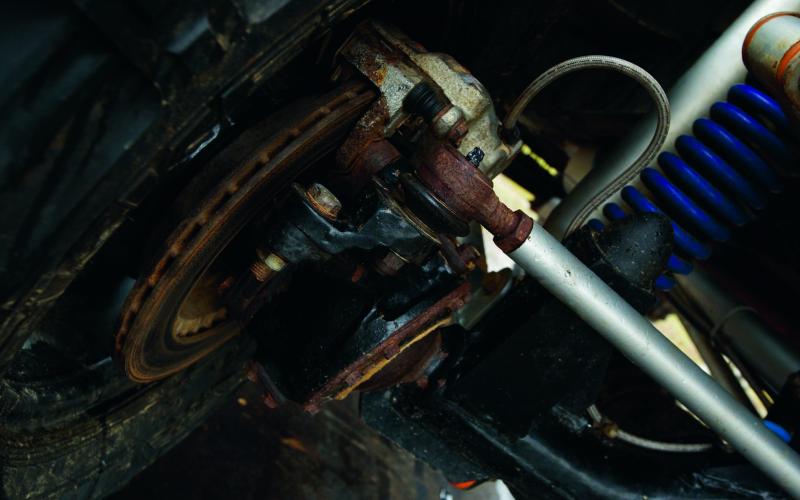

The system Richard built around them uses linkages made from CDS with a 6mm wall thickness, so it’s not very light but sure is strong. Front and rear radius arms are attached to the chassis at a pair of common mounting points, and centre links at each end run to the tops of the axle cases. So as to prevent binding on the bushes, the axle ends of the radius arms and the chassis ends of the centre links are attached using rotating joints, and up front the shocks are mounted ‘before’ these on the links themselves so as to follow the suspension faithfully throughout its full arc of movement. Finally, panhard rods are used front and rear to keep the axles in line.

The result? Brilliant, says Paul. ‘It’s very smooth, the way the suspension flexes. It keeps the car more balanced and stable.’ There’s no axle steer at all, and the angles of the diff noses don’t change however twisted the axles get. The springs are clamped top and bottom, as stability was more important to Paul than achieving the nth degree of wheel travel, but it still does a fine job of keeping its 34” Jungle Trekkers on the deck – and when it can’t, the ARBs he plundered from that donor Samurai mean it’s odds-on to keep moving anyway.

These are unusual in that they’re both rear units. They share the axles with a full set of heavy-duty Rock Assault halfshafts (plus CVs up front), whose size means they need to be used with a rear diff irrespective of which end they’re fitted in.

Up until the SJ got its 3-link conversion, Paul had it road-registered and used it for getting about when his everyday car didn’t seem interesting enough. Now, however, he’s decided to bestow it with full trailer queen status, which of course opens up a new set of options for winding up the MOT man.

You might be thinking of hydro-steer here, but a 34” Jungle Trekker isn’t too much of a struggle for the Vitara and Jimny PAS system to turn, and a Rob Storr high-steer set-up takes care of the extra height in what Paul thinks is about 5” of suspension lift. No, the main mod he’s made since taking the vehicle off the road has been a line-lock in the brakes.

These are most commonly used by drift and burnout fans to stop a car’s front wheels while the rears spin free, but you can also use them as a form of handbrake. Set up this way, it allows you to use the standard system as a hydraulic parking brake – very effective at stopping the vehicle from rolling away, though also for stopping even the most generous of testers from giving you a ticket.

Which is a shame in a way, because while many people trailer their vehicles to events simply because they’re too gross to ever see tarmac again, Paul’s SJ is once of the best-presented off-roaders you’ll ever see. Being a bodywork specialist helps him with this, obviously, but a childhood interest in a very different kind of modified car is responsible for one of the most unique touches to be found on this or any other 4x4.

Just take a look at those tail lights. ‘Back in my youth,’ says Paul, ‘I used to read custom car magazines. There’s a technique called “frenching” that’s popular in that scene.

‘I cut a 3” hole into the quarter panel and welded in a short length of tube, then I sunk the lights into that. It looks a bit out of the ordinary, and of course there’s no chance that

you’re ever going to break them. I used the same technique on the rear number plate, with the lights for it in the top of the recess.’

So it’s a looker, but with a practical streak running all the way through it. The first thing you see, of course, is just that it’s a looker, but make assumptions at your peril. ‘I quite enjoy turning up at events and seeing people saying “here’s another puddle-dodger,” but then ploughing into stuff!’ Cynics, eat your words…

And appearance does matter to Paul, to the extent that he’s made a positive decision not to pursue a level of off-road ability that would mean disfiguring his truck any further. ‘There are a lot of Suzukis that are more capable,’ he says, ‘but they don’t look original.’ He’s toyed with the idea of traybacking it, but most unusually for an SJ its floors, sills and so on are all still original. That’s a rarity and a half, and when so much of it is what came out of the factory all those years ago, it’s no wonder that he doesn’t want to mess with it.

Does that mean he’s done with the tinkering? Oh, no. Not even close. ‘I’ve owned it for more than ten years now, and it’s been evolving all that time. It’s never actually been finished!’

So what’s next on the list? A cheeky little increase in tyre size might be on the cards, with 35” Boggers his tyre of choice. He’s also planning another raid on Richard Wattam’s endless supply of ingenuity in the shape of a twin transfer case, which he’d use in conjunction with a 3-speed Vitara auto. Aside from that, he says, he just wants to use it a bit more.

A common problem for anyone with a modded 4x4, that. But few have put so much into getting their vehicle working right and looking right, and fewer still can claim to match the thoroughness of Paul’s approach on what is now just a toy. ‘Bodywork doesn’t matter to me as it’s such an easy fix,’ he says. ‘But I like to do everything so it’s a job you do once then forget about it. I have a think about it first and make sure I’m doing it so that it’s going to work for years to come.’

Changed days indeed from when a Saturday’s laning with a mate turned Paul from a man who’d never heard of off-roading into one who killed first a Lightweight and then an SJ410 in deep water. He’s learned what not to do, but more than anything else he already knew the way to create a Suzuki that makes people sit up and take notice. That doesn’t just mean getting Richard Wattam on the case, but as it illustrates he knew when to call in the experts, too. And what an SJ he’s got as a result.

SJ, WARN 8274, ROUGH COUNTRY SHOCKS, RALLY DESIGN SPRINGS, ROCKWATT SUSPENSION